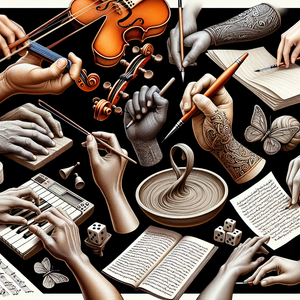

Tears on the Strings: The Emotional Odyssey of a Violin Connoisseur

My intimate connection with the violin began in a moment of serendipity when I was just 11 years old. My mother and I were wandering through a flea market when a sound stopped me in my tracks. It wasn’t even live music—just a faint recording emanating from a vendor's stall. Yet, it struck me like a lightning bolt. The piece was Bach’s *Chaconne* in D minor, performed by Jascha Heifetz. Even now, I can recall the way those notes soared and whispered, carrying both sorrow and hope in equal measure. It was as though the violin was speaking directly to me, telling me something I had forgotten about myself, something I hadn’t yet learned to articulate. That day, I begged my mother to buy that cassette tape. I played it endlessly, immersing myself in the world of violins. Years later, as I began studying music formally, I discovered something profound: my connection to the violin wasn’t merely emotional—it was physical. I could sense the subtlest imperfections in a violin's tone with uncanny precision. A slight misalignment of the soundpost, an imperceptible flaw in the varnish, or a string tuned just a hair too sharp would reveal itself to me like a whisper, demanding my attention.

The Ritual of Listening

To test a violin for its resonance is an act of reverence for me—a sacred ritual, equal parts art and science. When a musician or luthier entrusts me with an instrument, I begin with silence. I hold the violin in my hands, letting its weight and balance speak to me. My fingers trace the curves of its wood, feeling for anything that might betray its secrets. Next, I tune it. Every string must align perfectly, their pitches blending harmoniously before I even allow the bow to touch them. And then, I play the first note—a single, sustained tone, pure and uninterrupted. It is in this moment that the violin reveals itself. If the instrument is exceptional, its sound will bloom, filling the room with a resonance so profound it feels like sunlight spilling through a stained-glass window. These moments are overwhelming. Tears often well up in my eyes, but they are not tears of sadness or joy. They are tears of awe—at the perfection of sound, at the craftsmanship that allows wood, string, and bow to create something so transcendent. Yet, not every violin moves me. Some instruments fail to resonate, their voices muted or uneven. These moments are heartbreaking, as if the violin is crying out for help, longing to speak but unable to find its words. In such cases, I work closely with luthiers to diagnose the issue. Is it the bridge? The varnish? The wood itself? Together, we labor to restore the violin’s voice, to help it tell its story once more.

The Beauty and the Burden

This sensitivity to sound is both my gift and my curse. In moments of perfection—when I hear a master violinist perform, or when I discover an instrument whose voice seems to transcend the physical world—I feel a joy that is unparalleled. But this heightened sensitivity also makes me acutely aware of discordant or harsh sounds. The bane of my auditory existence? Phone alarms. There is something uniquely offensive about the harsh, synthetic blare of an alarm. Where a violin sings, an alarm screams. Its sound feels violent, an affront to the delicate balance of my auditory world. To cope, I’ve gone to great lengths to minimize my exposure. My phone is always set to vibrate, and I have replaced my morning alarm with a soft, melodic chime that mimics the plucking of violin strings. But in a world filled with electronic noise, alarms are inescapable, and each one feels like a betrayal of the beauty I dedicate my life to preserving.

Why It Matters

People often ask me why I care so deeply—why I let sound affect me so profoundly. My answer is simple: sound is emotion. A perfectly tuned violin can express what words cannot. It can carry you to places you thought you’d forgotten. It can make you weep for reasons you can’t explain. In a world that feels increasingly noisy and chaotic, these moments of pure resonance remind us of what it means to be human. And that is why my work matters—not just to me, but to the musicians and audiences I serve. By helping a violin find its voice, I am enabling it to connect, to communicate, to move people in ways that words never could.

The Unspeakable Truth of Sound

Victor Hugo once wrote, “Music expresses that which cannot be said and on which it is impossible to be silent.” This, to me, is the essence of the violin’s power. Its voice speaks to the unspeakable, offering solace, joy, and understanding in equal measure. So yes, I cry when I hear a perfectly tuned violin. I cry because it is beautiful, because it reminds me of the rare and precious things in life. And in a world filled with alarms and discord, those moments of resonance are more vital than ever.

In a world increasingly filled with noise and chaos, the moments of pure resonance offered by a perfectly tuned violin are a reminder of the rare and precious beauty in life. These moments connect us to our humanity, offering solace, joy, and understanding in ways words cannot.

Luthier (Violin Maker/Repair Specialist)

Independent workshops, orchestras, music schools, or renowned violin shops (e.g., Reuning & Son Violins, Maison Bernard)

Responsibilities

Craft, restore, and repair violins and other string instruments with precision, ensuring optimal sound quality and structural integrity.

Collaborate with musicians to customize instruments to meet their tonal preferences.

Required Skills

Expertise in woodworking, varnishing, and detailed craftsmanship.

Understanding of string instrument acoustics.

Ability to work with traditional tools and techniques.

Musical Acoustician

Research institutions, musical instrument companies (e.g., Yamaha, D'Addario), or consulting firms specializing in acoustics

Responsibilities

Analyze and optimize the acoustic properties of musical instruments, performance spaces, or recording studios.

Study sound propagation and resonance to create or improve instrument designs.

Required Skills

Strong background in physics and sound engineering.

Proficiency in acoustic modeling software.

Knowledge of materials and their impact on sound.

Orchestral Instrument Curator

Museums (e.g., The Met, Smithsonian), auction houses (e.g., Tarisio), or prominent orchestras

Responsibilities

Manage and maintain collections of rare or historical instruments, ensuring they are preserved and playable.

Work with musicians, collectors, and institutions to loan or exhibit instruments.

Required Skills

In-depth knowledge of instrument history and craftsmanship.

Skills in preservation techniques.

Ability to assess instrument value and condition.

Violin Sound Technician

Violin shops, orchestras, or as an independent consultant for professional musicians

Responsibilities

Assist musicians in achieving the desired tonal quality of their instruments by adjusting bridges, soundposts, and strings.

Conduct sound tests and provide feedback on resonance and projection.

Required Skills

Acute auditory sensitivity.

Hands-on knowledge of violin anatomy.

Experience working closely with musicians to understand artistic intent.

Music Historian (Specializing in String Instruments)

Academic institutions, music libraries, or cultural organizations (e.g., The Strad Magazine, Juilliard School)

Responsibilities

Research and document the history, cultural significance, and evolution of string instruments, with a focus on violins.

Publish articles, curate exhibitions, and give lectures on the subject.

Required Skills

Strong research and writing abilities.

Familiarity with classical music traditions.

Expertise in archival work and historical analysis.